The activity of editing newspapers has paradoxically been the economic area most affected by the consolidation of the communication society. This evolution is not just a story about the disappearance of some companies or about changes in consumption habits. It is, essentially, the story of a profound transformation in the way we access information, its quality, and ultimately, the health of our democracy. What disappears is not just a CAEN code, but an entire social structure and even a way of life.

In Romania, after 1990, newspapers and magazines were one of the first forms of manifestation of private initiative. The moment was one of civic and political effervescence. In the first days of 1990, against the backdrop of intensely tense political events, newspapers had daily circulations of over 1.5 million copies. Adevărul, România liberă, or Tineretul liber sold millions of copies daily. People eagerly sought information about what was happening in the country, about the changes that directly affected them. Private television stations had not yet appeared, and newspapers were the only alternative to a still heavily politicized TVR.

In the same year, the turnover of this economic segment had values that can be equated, for statistical amusement, with 600-800 million euros. (Such an exercise, equating revenues in a strong currency to collections in lei, is an artificial one, as the leu was not convertible at that time. Its value was set by government decree. At that exchange rate, no one would have sold a foreign currency).

More realistically, in the following years, after the introduction of convertibility, the market for daily newspapers can be estimated at about 140 million euros per year. Still, quite a few publications had circulations of several hundred thousand copies, with peaks reaching up to 600,000. The business model was mainly sustainable through direct sales. Contrary to trends in the global market, newspapers and magazines in Romania were largely financed by subscriptions and sales at kiosks. Subscriptions were still in the hundreds of thousands for the main publications, a sign of strong reader loyalty. Advertising, which in developed countries was the main source of funding, was still a debacle in Romania. It supplemented revenues but did not ensure sustainability.

However, galloping inflation, with values over 100% in those years, ruined capitalization and left companies vulnerable. From the end of the 1990s, a series of sales of companies that published written press began, both newspapers and magazines, and hostile takeovers were not absent. The lack of capital and general economic instability made many of these companies easy targets for investors who sometimes had more political than economic agendas.

And more history (but briefly)Obviously, the press did not start in 1990: that is when the companies or titles of publications that were to become relevant in the following period began.

Without delving into the actual history of the press, indissolubly linked to the stage of political and cultural development, the first daily newspapers appeared in Romania at the end of the 19th century. Initially, their circulation was only a few thousand copies, but it quickly reached tens of thousands.

In the interwar period, circulations grew again, and the large press trusts were relatively prosperous. However, the main evolution of the period was diversification. It characterized both magazines and other periodicals. The appearance of new titles became almost permanent, even though many had a short lifespan. Later, during communism, the number of newspapers was practically reduced to 3 (those at the national level), the first two – Scânteia and România liberă – with circulations of one million copies and even more. The newspapers reflected without nuances and without personality the propaganda of the PCR. Employees in enterprises were forced to subscribe.

Inheriting the infrastructure of communist newspapers, the major newspapers of the 1990s quickly lost their number of subscribers. Even under these conditions, they easily dominated the market. At the same time, many other titles appeared, not to develop new audience segments, but to serve directly and transparently the new political formations: FSN, PNTCD, PNL, etc.

Context: the 1990sThe economic collapse of the 1990s also affected newspaper sales. In the effort to reduce costs to maintain financial balance, daily newspapers abandoned many segments of current affairs, considered unprofitable, but which had played an essential role in defining the press. Culture and international politics pages were the first to be sacrificed. Extensive reports, investigations that required months of research, specialized commentary on complex issues became increasingly rare.

The effect was an immediate decrease in newspapers' ability to provide quality information with public utility. Implicitly: a decrease in the respectability of publications. The press gradually lost its role as an educator and provider of context, increasingly limiting itself to news of immediate impact, possibly politically subsidized, but superficial. The ability of newspapers to exercise a formative-educational function was seriously affected. The reader, who before could discover in the pages of a newspaper not only what was happening but also why and what the implications were for him and for society, began to receive only fragments of information, without depth or context.

The golden age and its illusionsThe economic stability after 2004, when Romania received the roadmap for joining the European Union, also led to a stabilization of the media market, including regarding newspapers. Turnover, human resources, and profitability experienced a certain consolidation. However, the profit margin remained small, at a maximum of 8-10%, and sometimes even went into the negative. Nevertheless, competition intensified. Many new titles appeared. For some publishers, the stake was to obtain a tool for political pressure, for others just a commercial vehicle for selling advertising. Sales at kiosks began to have an increasingly smaller importance in turnover, and subscriptions evaporated.

In the years 2004-2010, it was the golden age of the printed press. Circulations were much smaller than at the beginning of the 1990s, rated at only tens of thousands, with peaks of 150,000, compared to 500-600 thousand previously, but advertising had become a relevant source of funding. As a result, even free publications appeared. An emblematic example is the case of the newspaper Curentul, with sales below 5,000 copies, which becomes a free newspaper and suddenly distributes 120,000 copies, financed exclusively from advertising.

Other newspapers test other ways to increase their revenues. In 2009-2011, the most important of these was the distribution of books and DVDs, together with the edition. Essential libraries or collection films thus reach an audience that buys newspapers less for their informational value and more for their role as commercial vehicles. For a time, these marketing innovations mitigated and even counterbalanced the two crises threatening the field: the global crisis of 2009, which affected Romania with a delay, and the crisis caused by the internet and its role in the free or almost free distribution of news.

Let’s take the example of the newspaper Adevărul, one of the publications with the longest history in Romania. Founded in 1888, the newspaper had 5,000 copies in its first year of publication; it reached 32,000 in 1892. During communism, it ceased its activity.

In 1989, the main communist newspaper, Scânteia, had to change its name and revived the old title. The circulation was 1.5 million in 1990, dropping to 600,000 in 1993, reaching about 182,000 in 1998, 142,500 in 2001, and 107,000 in 2005. An unexpected collapse followed, caused by the departure of the core editorial team, led by Cristian Tudor Popescu. The circulation suddenly dropped to 26,200, only to return to 114,000 in 2009 and 121,000 in 2010 through the strategy of inserts of books and DVDs. However, after 2011, the collapse was rapid: 43,000 in 2011, 22,700 in 2012, 12,500 in 2013, 9,000 in 2015, 6,000 in 2017, reaching only 3,200 copies in 2025. (BRAT figures, taken directly or through articles from Adevărul and other publications).

The collapse of allAt one pace or another, all the dailies of the 2010s collapsed in the immediate following period.

Starting in 2011, none of the modern marketing vehicles seemed to function anymore. Circulations rapidly dropped to tens of thousands of copies per edition, then to thousands. The tabloids Ring and Click survived longer, having invented their own world, detached from public life, with personalities invented from nothing and with a sensationalism that still retains doses of popularity. This type of publication, focusing on scandal and sensation, found a niche audience that was not necessarily looking for information or relevance, but for entertainment and escape.

Magazines also had a similar business trend, but with smaller slopes, both in increases and decreases. In fact, companies that published newspapers often launched or bought less frequent periodicals to access specific audience niches or specific interests, such as classifieds or TV programs. Traditionally, the market for dailies and the magazine market have similar trends and values, with a slight plus for newspapers. However, having greater inertia, the magazine market had several years in which it was above that of dailies, a period that paradoxically coincided with the collapse of the printed press as a whole.

The increase in prices by 60% in those years did not sufficiently consolidate the business network, but instead led to an even sharper decline in circulations. In 2012-2013, circulations entered a vertical slope, with average decreases of 40-50% for quality dailies, but publishers amortized the loss through diversification: local editions, publishing supplements, and new price increases.

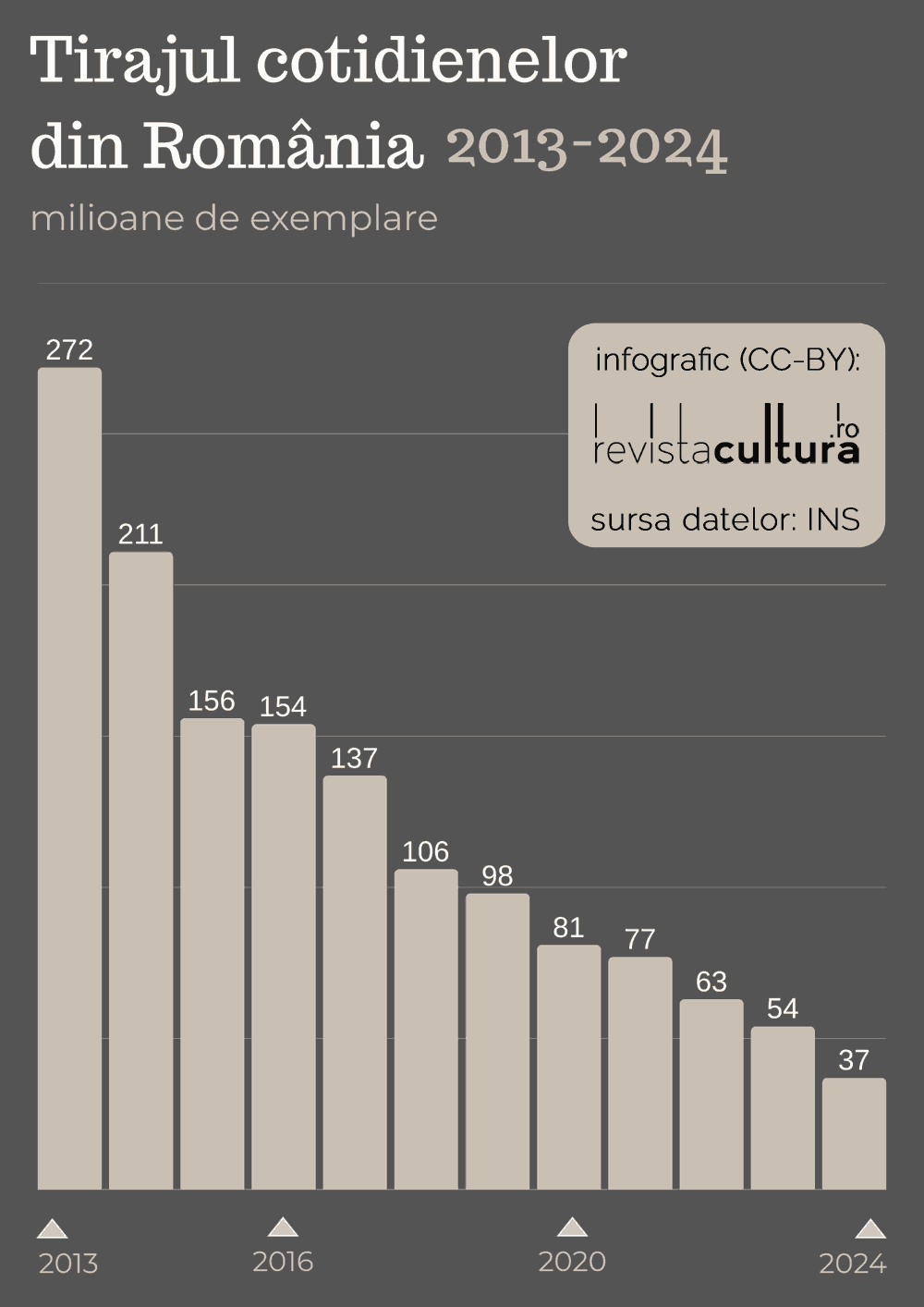

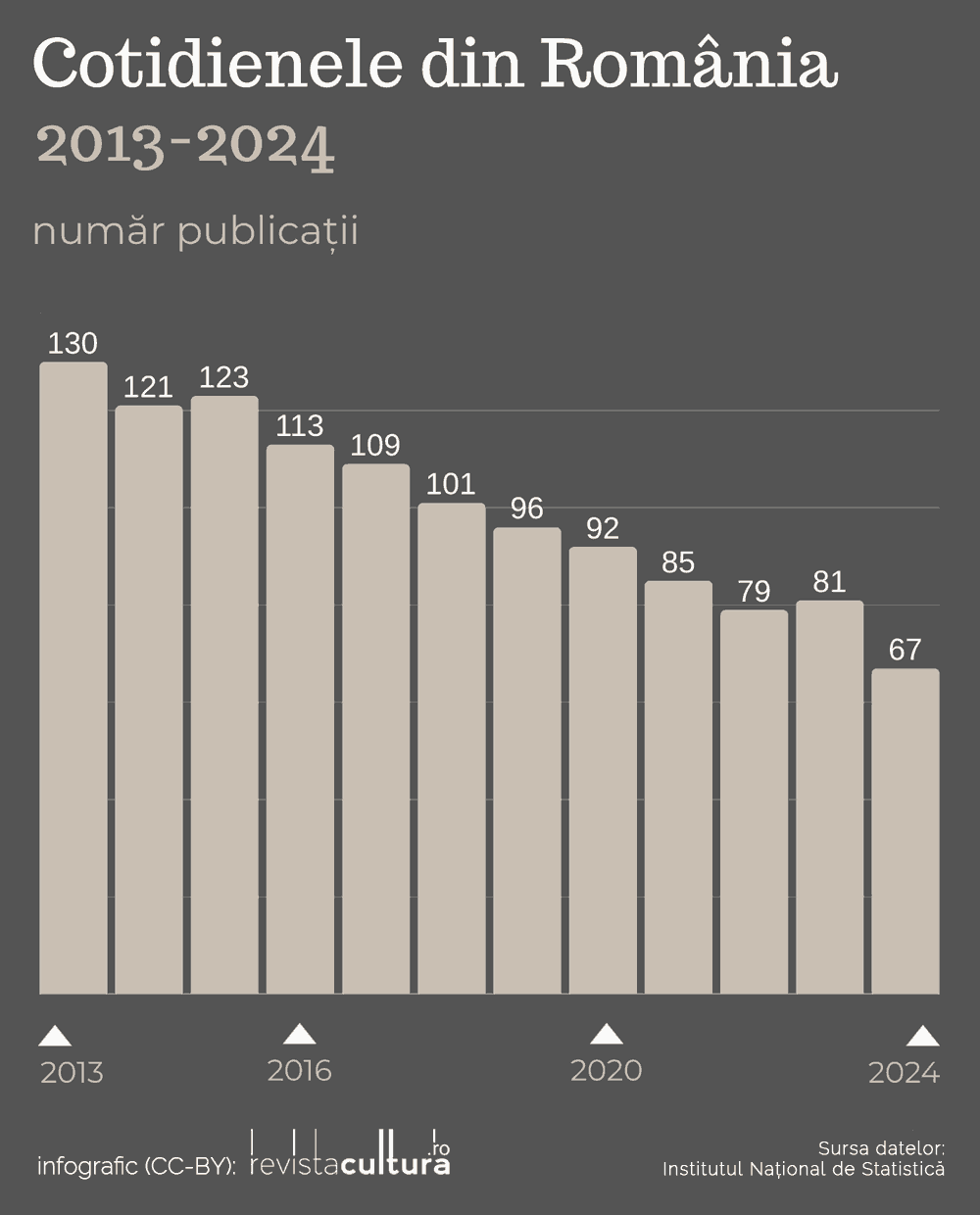

The figures speak for themselves. Nationally, the number of newspaper titles decreased from 130 in 2013 to just 67 in 2024, while the total annual circulation collapsed from over 272 million copies in 2013 to approximately 38 million in 2024. In just a decade, circulations have been reduced to less than half of the previous volume.

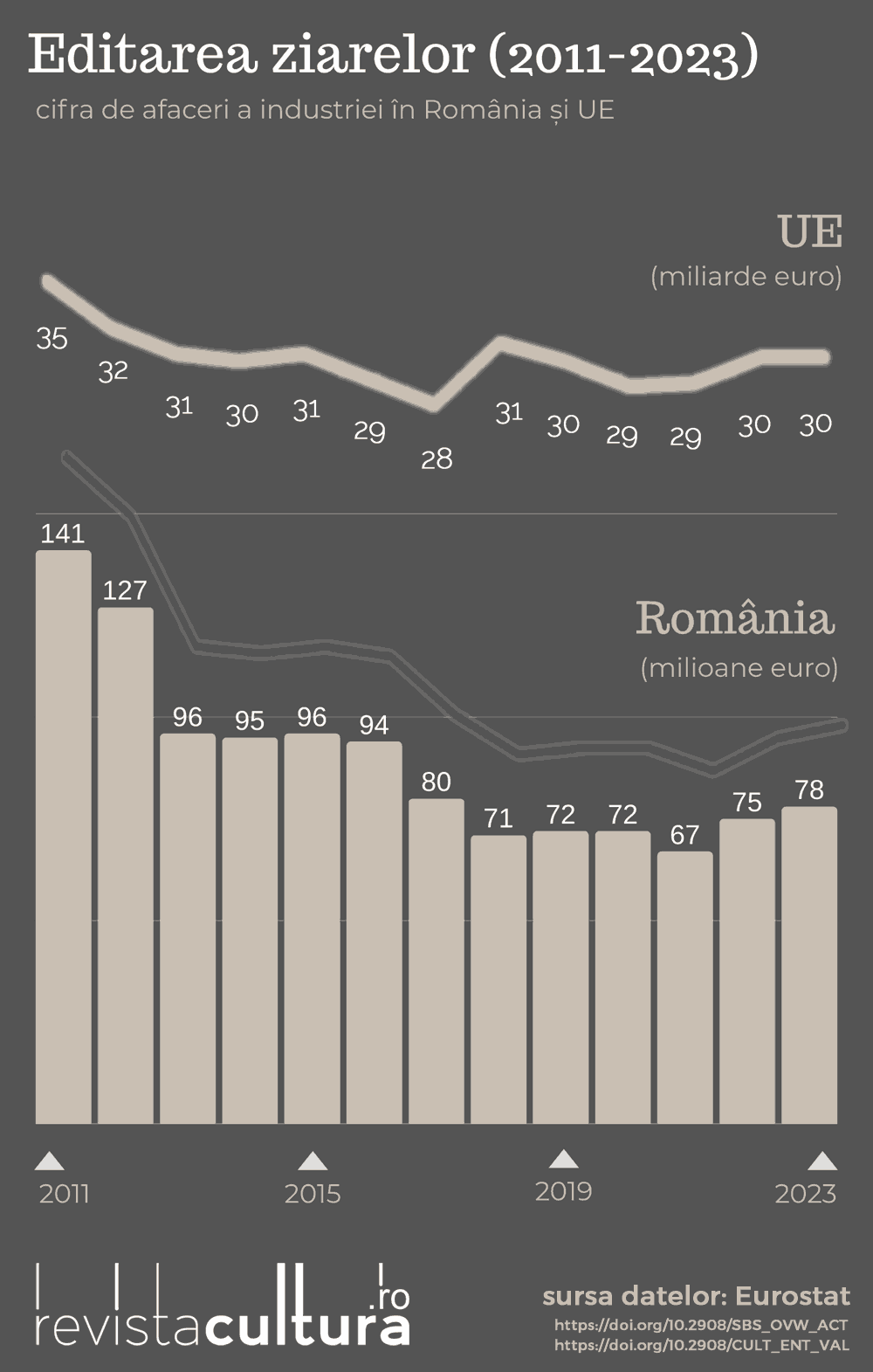

The editing of newspapers in Romania decreased from 141 million euros in 2011 to approximately 78 million in 2023. In the same period, at the European level, the market remained relatively constant, fluctuating around 30 billion euros. At the beginning of the period, in the EU-27, the quota was 35 billion euros (almost 250 times larger than that of Romania). At the end of the period: 30 billion (380 times the value of the Romanian market).

Overall, the trends in the Romanian press are the same as those at the global level, but in Romania they have been faster and more pronounced in speed and amplitude, reflecting both the greater economic vulnerability of Romanian companies and a sharper transition to digital consumption. Additionally, European dailies have managed to monetize online distribution at significantly higher levels, maintaining their turnover even under conditions of digital transformation. This is something that publications in Romania have only managed to a small extent.

After 2015, when the economy recovered and achieved remarkable growth rates, publications, especially printed ones, could not recover the circulations of the pre-crisis period. Online editions, some very good and with very low costs, proved too little attractive for advertising, thus failing to compensate for the collapse of turnover. Although online revenues are increasing year by year, the decrease in other components creates an apocalyptic landscape, in which only ruins of the old press institutions survive here and there.

Currently, only 1% of advertising expenditures are directed towards newspapers, a figure that says it all about the marginalization of this medium in the informational ecosystem.

The internet: savior – or the last drop?The continuity of newspapers online is undermined by the fact that this medium reduces information to its quality as content, without any other value axis than the audience. Newspapers are thus in competition with blogs, influencers, or sites without any informational value, the situation imposing almost complete abandonment of genres that are expensive in terms of resources: reporting, investigation, cover story. Instead, a first-level journalism dominates, with an increasingly reduced ethical concern.

Audience data from December 2025 for online publications in the News segment show a surprising reality. Of the top ten publications that have daily news content, even excluding sports publications, only three are engaged in newspaper editing. The rest are three television stations, two media representation companies, an online services company, and an NGO. In other words, news production has diversified enormously, but not necessarily in the direction of actors with expertise and journalistic tradition.

With a peak audience in 2019-2021, news websites have definitively eroded the audience of print publications. However, subsequently, they too recorded relative declines, leaving the segment increasingly less covered. The likely explanation is given by the increase in political content and microblogging on social networks, although there is no data to definitively certify this cause. People have not given up on information, but the written press, in any of its forms, print or web, has a decreasing audience share year by year.

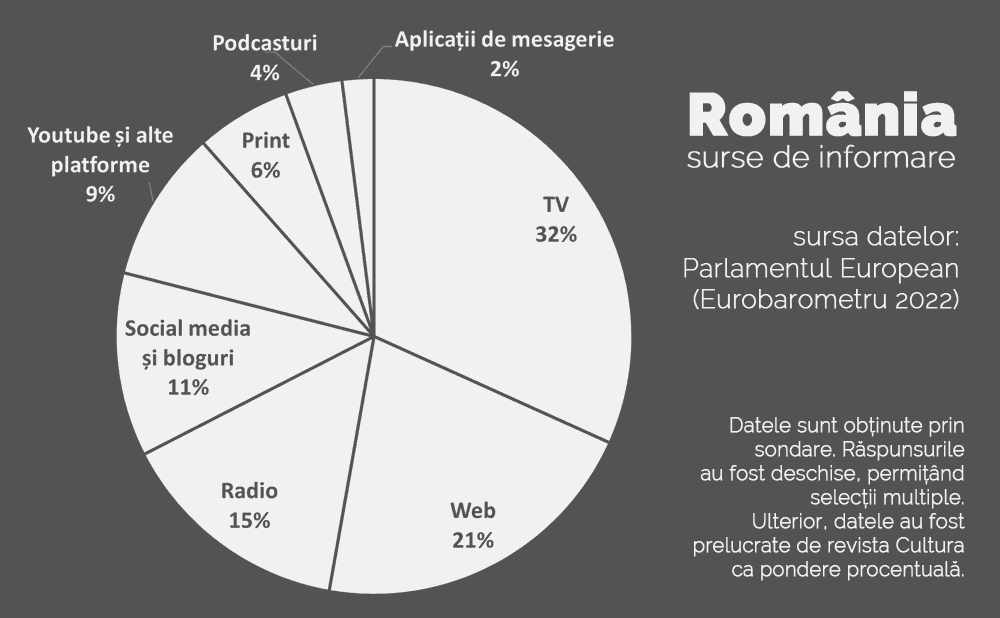

Where do we find information today?According to Eurobarometer data from 2022, the information sources of Romanians are distributed as follows: television dominates with 80%, followed by the web with 53%, radio with 37%, social networks and blogs with 29%, platforms like YouTube with 24%, printed press with only 15%, podcasts with 9%, and messaging applications with 5%. (The survey allowed the indication of multiple sources, hence the total exceeds 100%). It should be noted that current figures are likely lower for print and for web news content, given the continuous decline in circulations and, very recently, also in web audience for news content. Also, both the print section and the web section do not include only newspapers but also magazines, television, and other categories of current content providers.

In another vein, the indicated share – 15% for the printed press – is enormous compared to the reality of circulations. Even if we include magazines here, not just dailies, economic data and distribution figures strongly contradict this response, which can only be seen as a desirable one. In reality, print publications cannot have a share greater than 3-5% in the information mix, if we take into account measured audiences. In contrast, in opinion polls, respondents seem motivated to indicate such a source of information only for the prestige still superior compared to other sources.

The result is not only the tendency for the disappearance of an economic activity with a long tradition, newspaper editing, but also a degradation of the quality of information. Newspapers, with all their shortcomings, still provided verified, contextualized information, produced by professionals. The great advantage of the printed press is that it favors argument over emotion, allowing, essentially, a better understanding than other media (TV, radio, video).

Extensive reports allowed for a deep understanding of complex phenomena. Journalistic investigations brought to light issues that no one else was investigating. Or not investigating in a sustained manner. Specialized commentary helped readers understand the implications of current events and even created new perspectives and angles of understanding.

The disappearance of these journalistic genres affects not only the media industry but also the quality of critical thinking and democracy. A healthy democracy needs informed citizens, capable of understanding the complex problems facing society, evaluating political proposals, and participating in public debate with solid arguments. When information becomes superficial, fragmented, and lacking context, citizens' ability to participate meaningfully in democratic life is seriously diminished.

Quality written press, with all its high production costs, had the role of investigating, questioning, providing multiple perspectives, and educating. These functions cannot be fulfilled by fragments of content of 200 words, optimized for clicks, or by posts on social networks that overly simplify reality and stimulate partisanship and emotion to the detriment of critical spirit and balance.

A cultural and creative activityIt is significant that newspaper editing is integrated among the cultural and creative CAEN codes. This classification, since 2006 at the European level, is not arbitrary. The production of quality journalistic content is, by its nature, a cultural activity. The reclassification as ICC was a recognition of the production of added value through copyright, but also of the role of cultural vector in shaping culture, language, and identity. At the same time, it was a recognition of the social and democratic role that journalism has or should have.

In Romania, the way in which generalist publications have fulfilled this major role has not always been exemplary. The loss of respectability, through the promotion of cheap and easy content, has greatly contributed to the apocalypse that has affected the field. (The very high degree of functional illiteracy also has its contribution). Nevertheless, it is not coincidental that the publications that still resist are those that have assumed a clearer formative role and closer to the standards that the written press has refined over time. Even so, newspapers have been and remain, where they survive, archives of collective memory, documents of recent history, essential historical sources for the future.

The logic of classifying newspaper editing as a cultural and creative activity becomes evident when we look at the contribution that the press has to the cultural capital of a society. Newspapers are not just commercial vehicles for advertising or simple news providers. They still shape public discourse, set the agenda for important debates, and contribute to the ongoing education of citizens. Their loss is not just an economic change, but a major cultural loss.

Why "post"-apocalyptic?The figures from the last two years (possibly 2025 will also follow the same trend) indicate a stabilization of companies in the field. Even a slight increase. (However, this can be interpreted as the natural elasticity that occurs when the lower limit is reached, which does not guarantee recovery, but only the beginning of a new economic cycle).

The current landscape of the printed press is, indeed, post-apocalyptic. The old institutions have been swept away, traditional business models have failed, and new digital models have not yet managed to provide a viable alternative to support quality journalism. The question that remains open is whether they will find ways to rebuild a healthy informational ecosystem that serves the needs of a functional democracy, or whether they will continue on the current trajectory, in a world where information is abundant but superficial; free, but lacking real value; accessible, but without the capacity to accurately describe the world in which we live.

What is certain is that the way we access information has changed profoundly and, along with it, the quality of our democracy has also changed. In the current context, it is inconceivable that printed newspapers will return to Romania. Both consumption habits and distribution infrastructure are almost completely ruined. However, written press journalism, which allows for responsible, complex, and reasoned information, remains a poorly satisfied necessity at this moment. Sooner or later, demand will resuscitate supply.

Until then, however, we remain to look at the ruins of an industry that, at its peak, had an essential role in shaping our society.