Let's be serious: for many decades, the EU budget for the cultural sector – 0.000135% of the EU GDP – is/was a joke. Probably (we will never have the amount because the figures are, inherently, secret) the hybrid war to which European citizens are subjected (from Russia, from other "state actors", but also from a global religious-conservative network), has mobilized amounts that easily exceed such a budget.

The European Cultural Compass, as a strategic direction, and AgoraEU, as a funding program for the new direction, come to fill some of the gaps until now. The nearly fourfold increase in the budget is a (small) step in the right direction. For convenience, until now the EU has avoided a decisive commitment in the cultural sector. Through the new programs, the Commission is starting to take on an active role. Finally, culture is being pulled from the margins of European attention and is beginning to migrate to the center of concerns, where it belongs.

In the beginning was the Common Market. But the beginning is not over The European Union was built on economic foundations. In the 1950s, European countries, exhausted by war, chose commercial cooperation instead of armed conflict. The Common Market became the pragmatic solution: economic interdependence made war not only undesirable but also impractical. This logic has worked and continues to work remarkably well.

Over time, all other strategic projects have been built on this foundation. The Green Deal came as a natural extension of this economic approach. Expanded with NextGenerationEU, the program has become truly significant, maintaining its economic centrality. Environmental degradation, although it has profound social, philosophical, and cultural reverberations, remains essentially a problem generated by production and consumption models. The European response has been consistent: if the economy creates the problem, economic regulation must solve it. Climate budgets reflect this priority – the Climate Fund, Green Deal instruments, and the extension for post-Covid resilience amount to nearly one trillion euros.

Erasmus, the academic mobility program, was also a face of the common market. The priority: training the workforce. A completely marginal focus: promoting citizenship and civil values. Cohesion policy, agricultural programs, the social fund – all with an undeniable positive impact – maintain the same focus on primary needs.

The steps of the pyramid: prosperity without identity? However, there is a deeper logic in this evolution. When we look through the theoretical model provided by Maslow's hierarchy of needs, things do not look very good. The EU started from the bottom: economic security, stability, material well-being. These foundations were necessary and urgent. But once a certain level of economic security is reached, the stakes inevitably shift towards higher values: identity, meaning, creativity, self-actualization.

Here lies the problem: by dedicating itself almost exclusively to the lower steps of the pyramid – economy, environment, infrastructure – the EU has allowed culture to slip out of control. And culture is what defines human communities. After all, ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia built irrigation canals and ensured their survival or even prosperity. But they are not remembered for the canals. They are remembered for the art and culture they generated and that still contribute to human development. Prehistoric societies are still known as "material cultures" – because that is the only trace that still speaks about their identity. Through the culture they generated, they contributed to later stages of human development.

Beyond survival, the universal value of any society is given by the ability to generate culture, forms of art, and innovation that contribute to the perpetuation and development of humanity. In contemporary global competition, societies can only be truly prosperous if they are capable of artistic and technological creativity. Without this dimension, material prosperity becomes fragile, directionless, and vulnerable.

Culture: an uncomfortable problem for the "U" in EU Culture has, however, been treated with caution by European institutions. The reason is complex, but not hard to understand: European cultural heritage, although immense and rich, carries within it the scars of history. The foundational works of many nations celebrate resistance against other peoples who today are partners in the Union. This divergent dimension of classical culture risks generating tensions rather than strengthening unity.

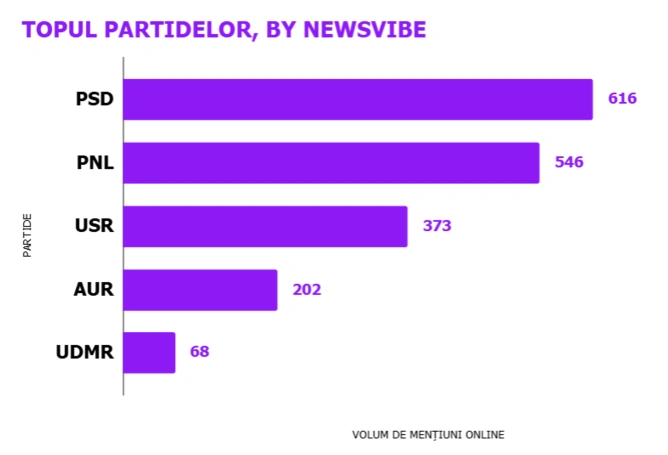

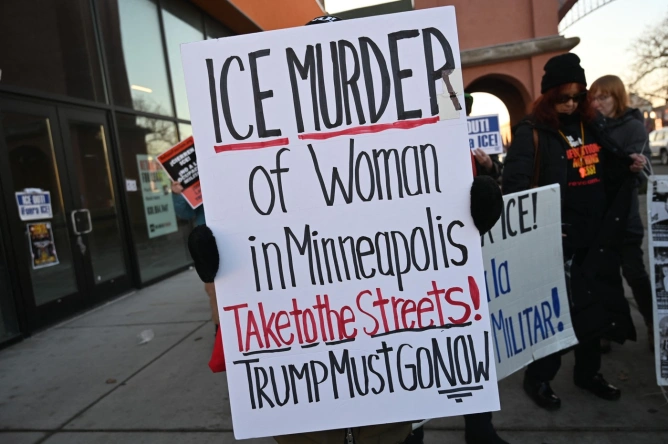

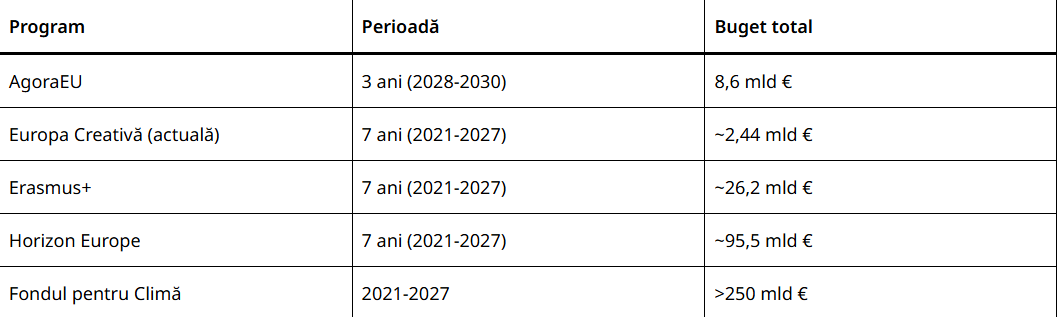

The European Commission's response has been one of prudent neutrality. Culture has received support, but in marginal and relatively external forms: artist mobility, international co-productions, translations, and circulation of contemporary works. Creative Europe, the main cultural program, had a budget of approximately 2.44 billion euros for the period 2021-2027 – a significant contrast compared to the ~95.5 billion for Horizon Europe (research) or ~26.2 billion for Erasmus+ (education). This is not to mention purely economic programs. This caution has left the European public cultural space vulnerable. In recent years, investments in external propaganda – both Russian and that of global religious-conservative organizations – have likely exceeded the entire budget of Creative Europe. Cultural narratives have been shaped by actors who did not have European cohesion in mind. On the contrary. In the absence of a clear and assertive cultural vision of its own, the EU has witnessed the fragmentation of public discourse and the erosion of democratic consensus in many member states.

Education: economic training or civic training? Similarly, education and research – areas in which the EU has lagged behind the US and China – have been viewed predominantly through an economic lens. Mobility programs, although valuable, are primarily oriented towards training a skilled workforce and less towards building a mentality and common knowledge at the European level. This is not a flaw in itself, but it is an unexplored opportunity for strengthening a European identity that transcends divergent national narratives.

Cultural Compass and AgoraEU: in search of the compass The metaphor of the European Compass is not coincidental. It comes at a time when Europe seems increasingly disoriented: rising extremism, eroding trust in institutions, social polarization, vulnerability to misinformation. In this context, the Cultural Compass and AgoraEU represent a signal for a paradigm shift in how the European Union thinks about the role of culture.

The Cultural Compass, launched in 2025, is not a funding program, but a strategic document that will guide European cultural policies and anchor culture in the future Multiannual Financial Framework 2028-2034. It is the first sign that Brussels treats culture not as an auxiliary field, but as a strategic component – a compass for the direction in which Europe wants to go.

In contrast, AgoraEU (2028-2030) comes with concrete resources: a total budget of 8.6 billion euros for three years – almost double the current pace. The program integrates culture, media, and civil society: Creative Europe – Culture strand: 1.8 billion € MEDIA+ strand: 3.2 billion € Democracy, Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values: 3.6 billion € The figures deserve to be contextualized. Compared to the EU's priority areas, the investment remains modest:

Culture receives more than before, but still substantially less than research, education, or the environment. We again leave aside purely economic programs. And the actual implementation of the Compass only begins in 2028 – a delay that, in the context of current social and cultural tensions, seems almost anachronistic.

Culture receives more than before, but still substantially less than research, education, or the environment. We again leave aside purely economic programs. And the actual implementation of the Compass only begins in 2028 – a delay that, in the context of current social and cultural tensions, seems almost anachronistic.

What does this change mean? With all its limitations, the Cultural Compass + AgoraEU suggests that the EU is beginning to understand that the European future cannot be built solely on economic regulations and environmental protection. Harmony with the planet first requires social harmony – and this is a cultural construct, not a commercial-customs one.

The programs attempt to do what the EU has long avoided: the participatory construction of common European values, strengthening a complex identity that includes national cultures and actively mediates beyond historical divergences. It is not about erasing national identities, but about adding a common dimension that enriches them and provides a common frame of reference.

A problem of cultural survival The contemporary global conflict is no longer just military or economic – it is also cultural, informational. Control of narratives influences societies as much as economic regulations. A Europe that is strong economically but lacks cultural cohesion, without the capacity to generate and disseminate its own narratives, remains vulnerable and, ultimately, irrelevant in global competition.

Culture is not an ornament, but the substance that makes a political community function in the long term and contributes to human development beyond its own borders. Europe has one of the richest cultural heritages in the world. Transforming it from a static heritage, often divergent between nations, into a lively dialogue that builds a common identity without standardizing differences, is a complex and urgent challenge.

Cultural Compass and AgoraEU do not solve everything. The effort remains far too small compared to the scale of the challenge and comes (somewhat) late. But it marks a fundamental recognition: if the European Union wants to remain a relevant and stable political force in the 21st century, it cannot be just a supermarket with strict rules and well-maintained irrigation channels. Roads and railways are good, but they are not enough. Beyond anything and above all, it must also be a community with values, a common vision, and the capacity for cultural creativity. After all, that is what makes the difference between civilizations that survive in heavily ideologized history textbooks and those that actually make history.